“But everyone is on a spectrum…we are all neurodiverse surely?”

Big Sigh.

Attempting to tackle our slippery nemesis…where does neurodiversity start and end?

I recently read a short article by a woman whose husband suffered from prosopagnosia, a condition which makes it hard to recognise names and faces.

She talked about the diversity present in society in general, about how neurodiversity was a spectrum, manifesting in many different ways and personality types, and that perhaps if we were more tolerant of this in general, society would be better off.

She mentions an “obsession” with neurodivergence which can “entrench victimhood and a lack of accountability” and says “the boundary between eccentricity and condition is a matter of clinical – and often subjective-judgment. “

Her concern that broadening definitions of neurodiversity risk undermining the experience and treatment of extreme disabilities is understandable, but for many, in particular high functioning neurodiverse individuals, we are on shaky ground here.

I think her discussion was highly relevant to one of the biggest causes of misunderstanding, and consequent undermining of the impact of neurodiversity that we are struggling with right now.

A lack of a clear notion where the boundaries into neurodiversity lie.

The exponential rise in both awareness and diagnoses of neurodiversity is a blessing and relief to those many people for whom life has unaccountably been impossibly hard for years, or decades.

We now know that conditions like ADHD are chronically underdiagnosed in the UK, but in contrast, discussions around, recognition of, and familiarity with neurodiversity has risen sharply, amongst families and friends, amongst employers and in the workplace, and in prominent content creation on social media.

Indeed many of these social media campaigns and personal accounts have genuinely helped people to see that problems they had no choice but to absorb all of their lives had another source that was staring them in the face.

Raising awareness, and providing people with the tools and vocabulary to identify and defend their differences, is of course, a fantastic thing – but its not without its problems.

“Everyone’s a bit ADHD though aren’t they”

“I do weird stuff like that all the time – I’m probably ADHD”

“The thing is, years ago, that was just called being a bit eccentric, quirky, you know, you didn’t have to have a name for it”

“Well being neurodiverse or having ADHD is just the in thing right now isn’t it…its what people want to call themselves”

“What is normal anyway? No one is typical, there’s no such thing”

How many things of this type have you heard recently? Read in an article? Perhaps have been said to your face. And they are so frustratingly, impossibly difficult to reply to effectively.

Because there are valid points in here.

But people who say these things have allowed themselves to notice the amount of information out there now about neurodiversity, without actually properly absorbing it.

What they are missing are the two key ingredients in the neurodiverse equation of SCALE and IMPACT. Most people who have discovered they have ADHD weren’t jumping up and down to get themselves this label, and what they sure as hell weren’t jumping up and down for was the list of symptoms that lead them to this realisation/ diagnosis.

One of the most difficult thoughts to refute from the above lists of unhelpful quotes, is that no-one is normal. Because this is of course, correct.

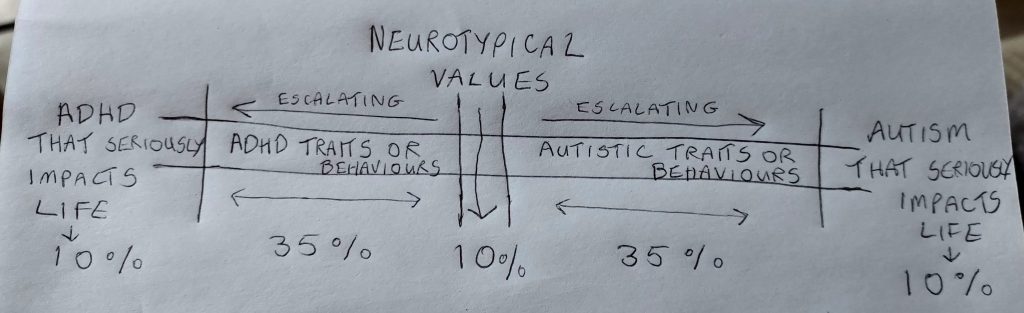

When I have tried to have this conversation with people in the past, I had a clear vision in my head of a simple, fluid scale of the neurotypes, which nevertheless had distinct and extreme ends where the level of neurodiversity began to seriously impact life.

ADHD’ers tend to see things very visually, so this often makes the most sense to us, but it really is surprisingly hard to verbally explain brain diagrams.

I therefore sincerely apologise in advance, I cannot draw, and I have previously been told that my left-handed scrawl looks like a cross between an old ladies and a small childs. This is what I pictured:

The point that my brain is endeavouring to express with its rudimentary stylings, is that “neurotypical” is surely a set of characteristics based on the median of all available neurotypes in society, right? So surely, this completely in the middle, absolutely standard, set of behaviours, will only actually be present in a fairly small percentage of people?

Yeah, maths may not be my strong point, but bear with me here.

Peoples personalities and characteristics, skills, emotions, tastes, cover such a wide range of variables, and I think that most people who are not neurodivergent fall somewhere within a huge 70% or so who are at varying points in the scale of diversity. Some may be very close to that standard median value, others may fall closer in their functioning or behaviour to the diverse end of the spectrum.

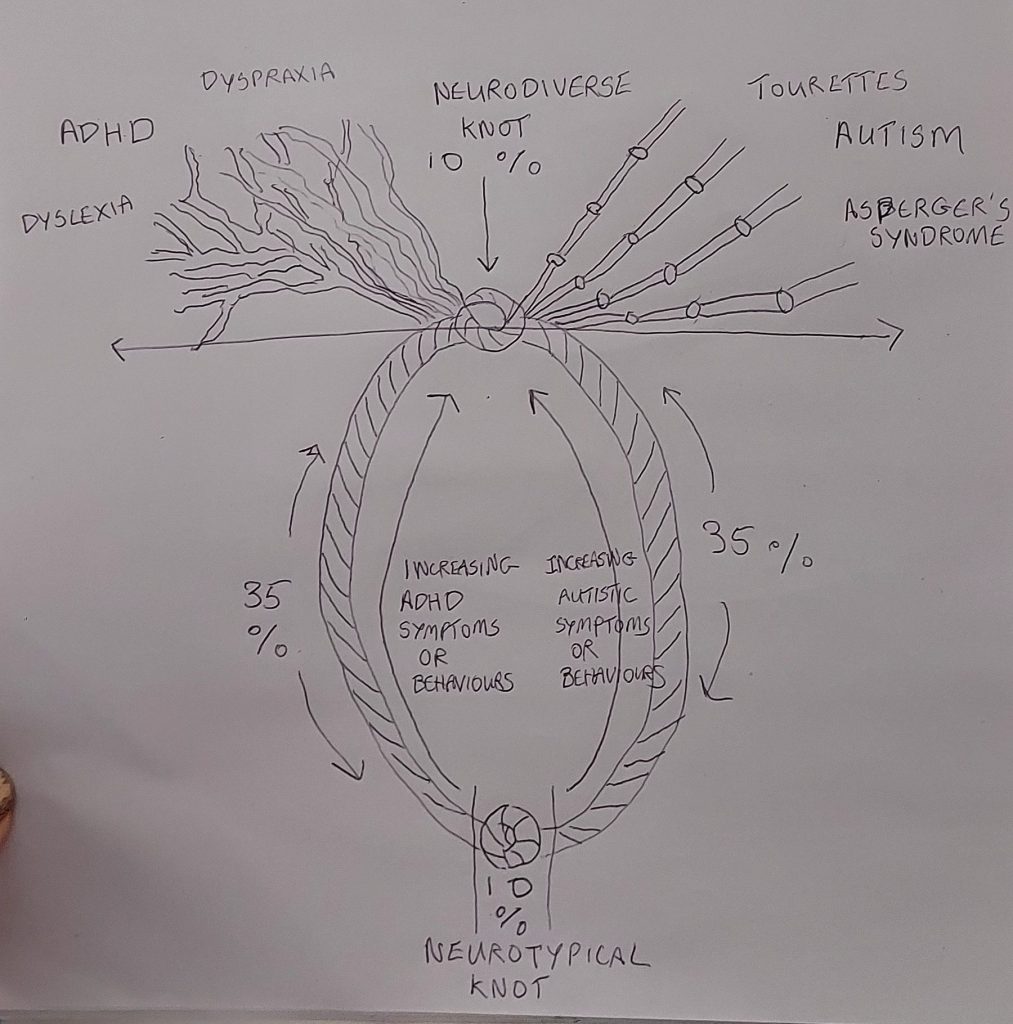

This crude diagram materialised in my brain early in my ADHD journey, while I was still trying to get to grips with what everything meant. Since then, I have learnt about the huge crossover between ADHD and Autism, and other forms of neurodiversity.

My brain diagram, which polarised ADHD and Autism as different ends of a spectrum, ceased to make satisfactory sense to me. Instead, clears throat, apologies again, my brain came up with something else.

Bear with me again.

The brain spectrum is represented by a piece of string, tied in a knot at the middle representing the neurotypical mid point. The two ends of the string go off different ways, representing the wide ranging selection we have within typical brains. As we get further away from the neurotypical knot however, the ends of the string converge into another knot, the neurodiverse knot. The knot that represents the crossover point into life affecting symptomatic neurodivergence.

It’s extremely crude, and the placement of example neurodiversities is random. The principally ADHD end of the string is represented by frayed, overlapping ends, and the autistic end by a series of knots, or blockages. But at the point where the strings converge…wait there..(“Never Cross the Strings!!”… sorry) a neurodivergent person may end up with various bits of string here there and everywhere.

Now, I was entirely oblivious to the fact that the second “diagram” I created bore some faint resemblances to parts of the female anatomy until my other half pointed this out. But by this stage I was too taken with the visual analogy of the knotted string that I wasn’t about to have another go, so I make no apologies for this.

I digress. The crucial thing here, is where does the tipping point come that shifts you into those extreme end categories, where people are actually labelled neurodivergent?

Of course, the whole thing can be very nuanced, and someones own perception of their brain wiring will be wholly subjective. But, crucially, I think whether a person tips into those extreme ends of the spectrum comes right back to the diagnostics we should all be aware of:

Does the difference in this person’s brain function seriously impact their daily life?

If it does, then yes, you fall within the fully neurodivergent ends of the spectrum.

Congratulations…you have passed the second knot.

Within these extreme ends, there is still a huge amount of variability in the amount and the way in which life is affected, from non-verbal, or severely disabled by a condition, to extremely high-functioning, gifted, Twice Exceptional people.

I have heard it said “I don’t let my neurodivergence define me”. And our neurodivergence is not all we are.

And yet – it is a massive part of us. How we were formed. It is how our brains work, and therefore intertwined with our thoughts, feelings, personalities – intrinsic to our very being.

This has to be embraced. But the severity of its difficulties must also be understood with the weight and significance they deserve.

I’m not suggesting this is widespread by any means, but those few people claiming that we all have a handful of neurodiverse characteristics and therefore dismissing the struggles of those who really are differently wired isn’t helpful.

What is helpful is to recognise that, of course, there is already a huge and wonderful spectrum in personalities and character traits within the neurotypical majority of our population.

In response to the question posed by the article about whether we are over-medicalising or naming neurodiversity, well, if the massive range of brain types falling under neurotypical were all regularly identifying themselves as neurodiverse, and seeking treatment for the same, then yes we would be. But I’m really not sure how often this is happening.

Perhaps some people feel this way due to the number of people who have years of obvious or well hidden mental health problems, dangerous masking and coping strategies, problems with self-medication with drugs and alcohol, who make look and seem very “normal” to them, that are finally coming forward to seek help.

For these people, the high-functioning neurodiverse – who are perhaps being sometimes unfairly judged as normal people jumping on a bandwagon – medical help, together with naming and explaining their condition, is as important as it is for those who are more obviously disabled and impaired in their function due to neurodiversity.

These people are often approaching their diagnosis with years of internalised trauma/ misunderstanding and co-existing conditions to start unravelling. Medical interventions and definitions can be crucial for us to get the help, recognition, or modifications to life that we may need.

Once you reach these ends of the spectrum, (or pass the second knot into neurodivergence), you have reached a point where it is not possible for you to live a normal “neurotypical” life, and your differences throw up enormous challenges.

We are not extreme versions of a personality type, we are something else altogether.

Here in the actual neurodiversiverse? I surely can’t be the first one to say that one – in the land beyond the second knot – life is hard. It can also be amazing. But above all, it is different. At this point, very simply, our brains are different to yours.

Do you struggle with this argument with friends or colleagues? Do you have a chosen explanation or visual to help others understand the level of your difference? Let me know in the comments below.

Thoughts or ramblings welcome here…